Methanol

- This page was taken from the Wikipedia article, accessed January 21, 2007.

| Methanol | |

|---|---|

Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| General | |

| Systematic name | methanol |

| Other names | hydroxymethane methyl alcohol wood alcohol carbinol |

| Molecular formula | CH3OH |

| SMILES | CO |

| Molar mass | 32.04 g/mol |

| Appearance | colourless liquid |

| CAS number | [67-56-1] |

| Properties | |

| Density and phase | 0.7918 g/cm3, liquid |

| Solubility in water | Fully miscible |

| Melting point | -97 °C (176 K) |

| Boiling point | 64.7 °C (337.8 K) |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~ 15.5 |

| Viscosity | 0.59 mPa·s at 20 °C |

| Structure | |

| Molecular shape | Tetrahedral and Bent |

| Dipole moment | 1.69 D (gas) |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | External MSDS |

| EU classification | Flammable (F) Toxic (T) |

| NFPA 704 | |

| R-phrases | Template:R11, Template:R23/24/25, Template:R39/23/24/25 |

| S-phrases | Template:S1/2, Template:S7, Template:S16, Template:S36/37, Template:S45 |

| Flash point | 11 °C |

| RTECS number | PC1400000 |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Structure & properties | n, εr, etc. |

| Thermodynamic data | Phase behaviour Solid, liquid, gas |

| Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS |

| Related compounds | |

| Related alkanols | ethanol butanol |

| Related compounds | chloromethane methoxymethane |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25°C, 100 kPa) Infobox disclaimer and references | |

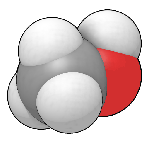

Methanol, also known as methyl alcohol, carbinol, wood alcohol or wood spirits, is a chemical compound with chemical formula CH3OH. It is the simplest alcohol, and is a light, volatile, colourless, flammable, poisonous liquid with a distinctive odor that is somewhat milder and sweeter than ethanol (ethyl alcohol). It is used as an antifreeze, solvent, fuel, and as a denaturant for ethyl alcohol.

Methanol is produced naturally in the anaerobic metabolism of many varieties of bacteria. As a result, there is a small fraction of methanol vapor in the atmosphere. Over the course of several days, atmospheric methanol is oxidized by oxygen with the help of sunlight to carbon dioxide and water.

Methanol burns in air forming carbon dioxide and water:

- 2 CH3OH + 3 O2 → 2 CO2 + 4 H2O

A methanol flame is almost colorless. Care should be exercised around burning methanol to avoid burning oneself on the almost invisible fire.

Because of its poisonous properties, methanol is frequently used as a denaturant additive for ethanol manufactured for industrial uses— this addition of a poison economically exempts industrial ethanol from the rather significant 'liquor' taxes that would otherwise be levied as it is the essence of all potable alcoholic beverages. Methanol is often called wood alcohol because it was once produced chiefly as a byproduct of the destructive distillation of wood. It is now produced synthetically by a multi-step process. In short, natural gas and steam are reformed in a furnace to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide; then, hydrogen and carbon monoxide gases react under pressure in the presence of a catalyst. The reforming step is endothermic and the synthesis step is exothermic.

History

In their embalming process, the ancient Egyptians used a mixture of substances, including methanol, which they obtained from the pyrolysis of wood. Pure methanol, however, was first isolated in 1661 by Robert Boyle, who called it spirit of box, because he produced it via the distillation of boxwood. It later became known as pyroxylic spirit. In 1834, the French chemists Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Eugene Peligot determined its elemental composition. They also introduced the word methylene to organic chemistry, forming it from Greek methy = "wine" + hŷlē = wood (patch of trees). Its intended origin was "alcohol made from wood (substance)", but it has Greek language errors. The term "methyl" was derived in about 1840 by back-formation from methylene, and was then applied to describe "methyl alcohol". This was shortened to "methanol" in 1892 by the International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature. The suffix -yl used in organic chemistry to form names of radicals, was extracted from the word "methyl".

In 1923, the German chemist Matthias Pier, working for BASF developed a means to convert synthesis gas (a mixture of carbon oxides and hydrogen) into methanol. This process used a zinc chromate catalyst, and required extremely vigorous conditions—pressures ranging from 30–100 MPa (300–1000 atm), and temperatures of about 400 °C. Modern methanol production has been made more efficient through use of catalysts (commonly copper) capable of operating at lower pressures.

The use of methanol as a motor fuel received attention during the oil crises of the 1970s due to its availability and low cost. Problems occurred early in the development of gasoline-methanol blends. As a result of its low price some gasoline marketers over blended. Others used improper blending and handling techniques. This led to consumer and media problems and the last time out of methanol blends. However, there is still a great deal of interest in using methanol as a neat fuel. The flexible-fuel vehicles currently being manufactured by General Motors, Ford and Chrysler can run on any combination of ethanol, methanol and/or gasoline. Neat alcohol fuels will become more widespread as more flexible-fuel automobiles are manufactured.

In 2006 astronomers using the MERLIN array of radio telescopes at Jodrell Bank Observatory discovered a huge cloud of methanol in space. The cloud measures 300 billion miles across, and is emitted from stars as they form.

Production

Today, synthesis gas is most commonly produced from the methane component in natural gas rather than from coal. Three processes are commercially practiced. At moderate pressures of 1 to 2 MPa (10–20 atm) and high temperatures (around 850 °C), methane reacts with steam on a nickel catalyst to produce syngas according to the chemical equation:

This reaction, commonly called steam-methane reforming or SMR, is endothermic and the heat transfer limitations place limits on the size of the catalytic reactors used. Methane can also undergo partial oxidation with molecular oxygen to produce syngas, as the following equation shows:

this reaction is exothermic and the heat given off can be used in-situ to drive the steam-methane reforming reaction. When the two processes are combined, it is referred to as autothermal reforming. The ratio of CO and H2 can be adjusted by using the water-gas shift reaction,

to provide the appropriate stoichiometry for methanol synthesis.

The carbon monoxide and hydrogen then react on a second catalyst to produce methanol. Today, the most widely used catalyst is a mixture of copper, zinc oxide, and alumina first used by ICI in 1966. At 5–10 MPa (50–100 atm) and 250 °C, it can catalyze the production of methanol from carbon monoxide and hydrogen with high selectivity

It is worth noting that the production of synthesis gas from methane produces 3 moles of hydrogen for every mole of carbon monoxide, while the methanol synthesis consumes only 2 moles of hydrogen for every mole of carbon monoxide. One way of dealing with the excess hydrogen is to inject carbon dioxide into the methanol synthesis reactor, where it, too, reacts to form methanol according to the chemical equation

Although natural gas is the most economical and widely used feedstock for methanol production, other feedstocks can be used. Where natural gas is unavailable, light petroleum products can be used in its place. The South African firm Sasol produces methanol using synthesis gas from coal.

Uses

Methanol is used on a limited basis to fuel internal combustion engines, mainly by virtue of the fact that it is not nearly as flammable as gasoline. Methanol blends are the fuel of choice in open wheel racing circuits like Champcars, as well as in radio controlled model airplanes (required in the "glow-plug" engines that primarily power them), cars and trucks. Dirt circle track racecars such as Sprint cars, Late Models, and Modifieds use methanol to fuel their engines. Drag racers and mud racers also use methanol as their primary fuel source. Methanol is required with a supercharged engine in a Top Alcohol Dragster and, until the end of the 2005 season, all vehicles in the Indianapolis 500 had to run methanol. Mud racers have mixed methanol with gasoline and nitrous oxide to produce more power than gasoline and nitrous oxide alone.

Methanol is a traditional ingredient in methylated spirit or denatured alcohol.

During World War II, methanol was used as a fuel in several Nazi Germany military rocket designs, under name M-Stoff, and in a mixture as C-Stoff.

One of the drawbacks of methanol as a fuel is its corrosivity to some metals, including aluminium. Methanol, although a weak acid, attacks the oxide coating that normally protects the aluminium from corrosion:

- 6 CH3OH + Al2O3 → 2 Al(OCH3)3 + 3 H2O

The resulting methoxide salts are soluble in methanol, resulting in clean aluminium surface, which is readily oxidised by some dissolved oxygen. Also the methanol can act as an oxidiser:

- 6 CH3OH + 2 Al → 2 Al(OCH3)3 + 3 H2

So the corrosion continues until the metal is eaten away.Template:Reference needed

When produced from wood or other organic materials, the resulting organic methanol (bioalcohol) has been suggested as renewable alternative to petroleum-based hydrocarbons. However, one cannot use BA100 (100% bioalcohol) in modern petroleum cars without modification. Methanol is also used as a solvent and as an antifreeze in pipelines. The largest use of methanol by far, however, is in making other chemicals. About 40% of methanol is converted to formaldehyde, and from there into products as diverse as plastics, plywood, paints, explosives, and permanent press textiles.

In some wastewater treatment plants, a small amount of methanol is added to wastewater to provide a food source of carbon for the denitrification bacteria, which convert nitrates to nitrogen.

Also in early 1970's Methanol to gasoline process was developed by Mobil, which produces gasoline ready for use in vehicles, one industrial facility was built in New Zealand in 1980's.

In the 1990s, large amounts of methanol were used in the United States to produce the gasoline additive methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). The 1990 Clean Air Act required certain major cities to use MTBE in their gasoline to reduce photochemical smog. However, by the late 1990s, it was found that MTBE had leaked out of gasoline storage tanks and into the groundwater in sufficient amounts to affect the taste of municipal drinking water in many areas. Moreover, MTBE was found to be a carcinogen in animal studies. In the resulting backlash, several states banned the use of MTBE, and its future production remains uncertain.

Direct-methanol fuel cells are unique in their low temperature, atmospheric pressure operation, allowing them to be miniaturized to an unprecedented degree. This, combined with the relatively easy and safe storage and handling of methanol may open the possibility of fuel cell-powered consumer electronics.

Other chemical derivatives of methanol include dimethyl ether, which has replaced chlorofluorocarbons as an aerosol spray propellant, and acetic acid.

There are now plans to use the chemical in eco-friendly fuel cells for laptop computers, the cells will break down methanol via an electrochemical process. [1]

Health and safety

Methanol is intoxicating but not directly poisonous. It is toxic by its breakdown (toxication) by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver by forming formic acid and formaldehyde which cause blindness by destruction of the optic nerve. [3] Methanol ingestion can also be fatal due to its CNS depressant properties in the same manner as ethanol poisoning. It enters the body by ingestion, inhalation, or absorption through the skin. Fetal tissue will not tolerate methanol. Dangerous doses will build up if a person is regularly exposed to vapors or handles liquid without skin protection. If methanol has been ingested, a doctor should be contacted immediately. The usual fatal dose: 100–125 mL (4 fl oz). Toxic effects take hours to start, and effective antidotes can often prevent permanent damage. This is treated using ethanol or fomepizole.[2] Either of these drugs acts to slow down the action of alcohol dehydrogenase on methanol by means of competitive inhibition, so that it is excreted by the kidneys rather than being transformed into toxic metabolites. Though it is miscible with water, methanol is very hard to wash off the skin; it is best to treat methanol like gasoline.

The initial symptoms of methanol intoxication are those of central nervous system depression: headache, dizziness, nausea, lack of coordination, confusion, drowsiness, and with sufficiently large doses, unconsciousness and death. The initial symptoms of methanol exposure are usually less severe than the symptoms resulting from the ingestion of a similar quantity of ethyl alcohol.

Once the initial symptoms have passed, a second set of symptoms arises 10–30 hours after the initial exposure to methanol: blurring or complete loss of vision, together with acidosis. These symptoms result from the accumulation of toxic levels of formate in the bloodstream, and may progress to death by respiratory failure. The ester derivatives of methanol do not share this toxicity.

Ethanol is sometimes denatured (adulterated), and thus made undrinkable, by the addition of methanol. The result is known as methylated spirit or "meths" (UK use). (The latter should not be confused with meth, a common abbreviation for methamphetamine.)

Pure methanol has been used in open wheel racing since the mid-1960s. Unlike petroleum fires, methanol fires can be extinguished with plain water (while methanol is less dense than water, they are miscible, and the addition of water will cause the fire to use its heat to boil the water). In addition, a methanol-based fire burns invisibly, unlike gasoline, which burns with thick black smoke. If a fire occurs on the track, there is no smoke to obstruct the view of fast approaching drivers. The decision to permanently switch to methanol in American Indycar racing is directly linked to a devastating crash and explosion at the 1964 Indianapolis 500 which killed drivers Eddie Sachs and Dave MacDonald.

One concern with the addition of methanol to automotive fuels is highlighted by recent groundwater impacts from the fuel additive methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). Leaking underground gasoline storage tanks created MTBE plumes in groundwater that eventually adulterated well water. Methanol's high solubility in water raises concerns that similar well water contamination could arise from the widespread use of methanol as an automotive fuel.

See also

- Liquid fuels

- List of Stoffs

- Methanol (data page)

- Methanol economy

- Aspartame

- TBA

- Methanol to gasoline

References

- Robert Boyle, The Sceptical Chymist (1661) – contains account of distillation of wood alcohol.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 005700

- The Methanol Institute Industry trade group, lots of information on methanol's use in fuel cells and as an alternative fuel.

- National Pollutant Inventory - Methanol Fact Sheet

- Molview from bluerhinos.co.uk See Methanol in 3D

- Methanol Discovered in Space